Vascular disease overlooked contributor to dementia, UNM researcher finds

Vascular dementia–cognitive impairment caused by disease in the brain’s small blood vessels-is a widespread problem, but it has not been as thoroughly studied as Alzheimer’s disease, in which abnormal plaques and protein tangles are deposited in neural tissue.

One researcher at The University of New Mexico hopes to change that.

In a newly published paper featured by the editors of the American Journal of Pathology, Elaine Bearer, MD, PhD, the Harvey Family Endowed and Distinguished Professor in the UNM School of Medicine’s Department of Pathology, sets out a new model for characterizing and categorizing different forms of vascular dementia.

She hopes this approach will help researchers to better understand the various forms of the disease and find effective treatments.

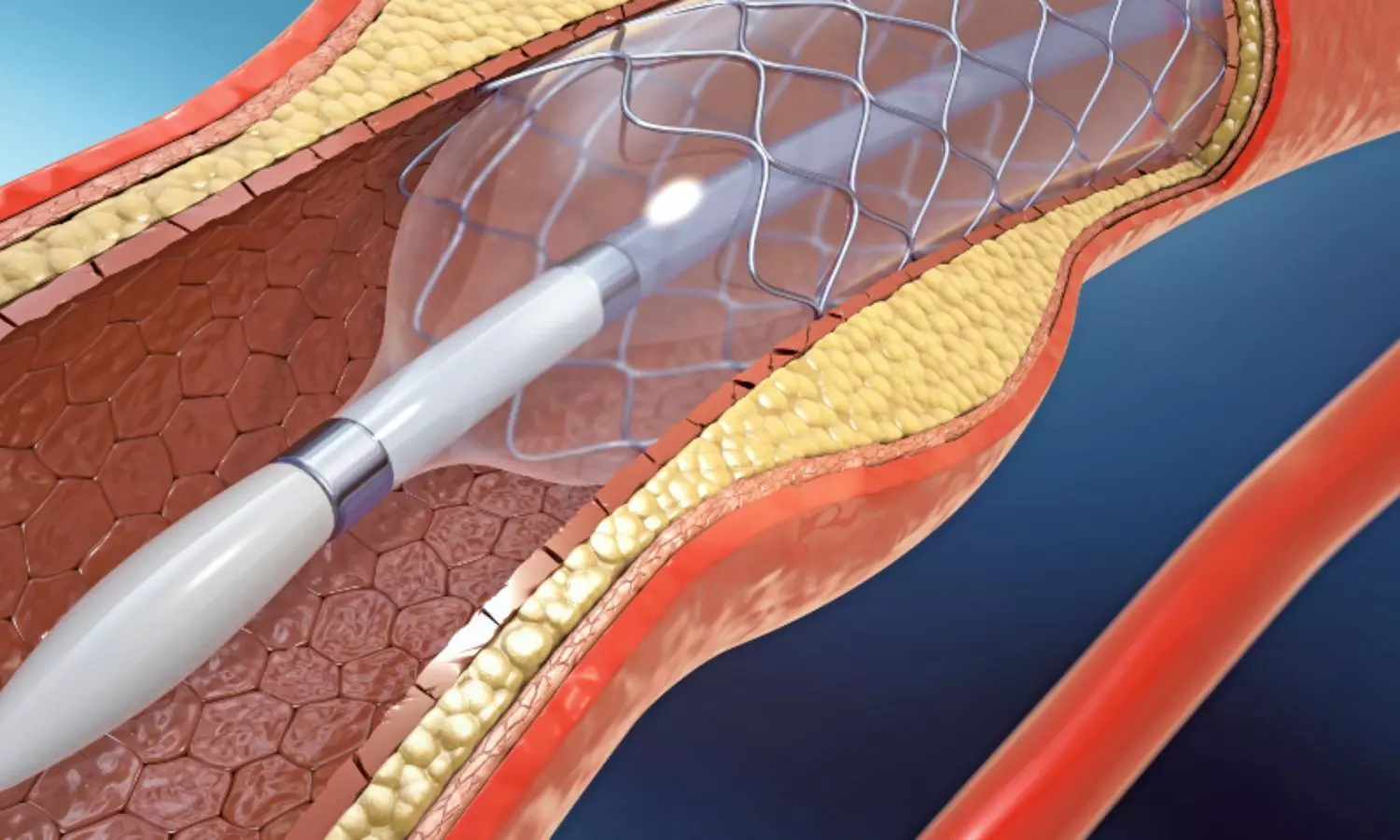

Conditions like hypertension, atherosclerosis and diabetes have been linked to vascular dementia, but other contributing causes, including the recent discovery of significant quantities of nano– and microplastics in human brains, remain poorly understood, Bearer said.

“We have been flying blind,” she said. “The various vascular pathologies have not been comprehensively defined, so we haven’t known what we’re treating. And we didn’t know that nano– and microplastics were in the picture, because we couldn’t see them.”

Bearer identified 10 different disease processes that contribute to vascular-based brain injury, typically by causing oxygen or nutrient deficiency, leakage of blood serum and inflammation or decreased waste elimination. These cause tiny strokes that harm neurons. She lists new and existing experimental techniques, including special stains and novel microscopy, to detect them.

For the paper, Bearer used a specialized microscope to meticulously study tissue from a repository of brains donated by the families of New Mexicans who had died with dementia, employing stains that highlighted the damaged blood vessels. Surprisingly, many patients diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease also had disease in the small blood vessels of the brain.

“We suspect that in New Mexico maybe a half of our Alzheimer’s people also have vascular disease,” she said.

Bearer contends a methodical approach to identifying different forms of vascular dementia will help neurologists and neuropathologists more accurately score the severity of the disease in both living and deceased patients and advance the search for potential treatments — and even cures. To make that happen, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) has raised the possibility of forming a consensus group of leading neuropathologists to work out a new classification and scoring system, she said.

Meanwhile, a fresh area of concern is the unknown health consequences of nano– and microplastics in the brain, Bearer said.

“Nanoplastics in the brain represent a new player on the field of brain pathology,” she said. “All our current thinking about Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias needs to be revised in light of this discovery.”

“What I’m finding is that there’s a lot more plastics in demented people than in normal subjects,” she said. “It seems to correlate with the degree and type of dementia.”

The quantity of plastics also was associated with higher levels of inflammation, she said.

Bearer’s work builds on years of collaboration with Gary Rosenberg, MD, professor of Neurology and director of the UNM Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (ADRC), which won a five-year $21.7 million NIH grant in 2024 that supported Bearer’s research. Rosenberg, a longtime chair of the UNM Department of Neurology and also director of the UNM Center for Memory & Aging, has published extensively on the association of vascular disease with dementia symptoms.

“When we started thinking about putting this ADRC together, I thought one of the things I should look at is the vasculature, because nobody’s done it systematically and comprehensively, and we have a world’s expert here at UNM,” Bearer said.

“Describing the pathological changes in this comprehensive way is really new. What I’m hoping will come out of this paper is working with other neuropathology ADRC cores across the country to develop consensus guidelines for classifying vascular changes and the impact of nano– and microplastics on the brain.”

Reference:

Bearer, Elaine L., Exploring Vascular Contributions to Cognitive Impairment: Small-Vessel Disease of White Matter and Microplastics/Nanoplastics, American Journal Of Pathology, DOI: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2025.07.007.

Powered by WPeMatico